A minority

… is the only government that will bring political change

With even Andrew Bolt giving up on Dutton, it would appear his goose is cooked. The Coalition can no longer ignore its own failings, Bolt writes, and it has no overall vision: “Dutton’s campaign is quickly collapsing”. Unusually, Bolt appears to be right.

But if a Coalition collapse portends a Labor majority, this is nothing to be sanguine about. As seen in the longterm slide of the major-party vote, Australians are increasingly dissatisfied with the entrenched duopoly. And no wonder. A Labor majority government promises only more of the same.

The Labor government under Albanese, as I’ve written before, is allergic to bravery and incapable of bold and imaginative leadership. The problem is both structural and deeply behavioural. Why would we expect any different from a future Labor majority? That would be, as per the famously misattributed quote, the definition of insanity.

There is another possibility: a minority Labor government. This outcome has long been the subject of intense scaremongering in the mainstream media and from the duopoly parties, which is perhaps the best reason to barrack for it. A minority government is the only chance for significant political change in this country.

The most common Labor objection to minority government is something like this: stability is always preferable to chaos. This sounds like a fair assertion (even despite the achievements of the Gillard government), but the underlying logic is fundamentally wrong. Consultation beyond the major parties doesn’t guarantee chaos. It guarantees different viewpoints, broader debates and a more rigorous testing of ideas. It means that bad ideas don’t become untested laws, and that captured political parties or arrogant leaders can’t run roughshod over proper processes. Sounds like … democracy.

The other common defence by Labor people of their current majority government is that you can’t achieve everything in your first term, so give us time. But Labor hasn’t even tried to achieve big things. In fact the Labor government spent its first term avoiding serious reform, such that giant swathes of policy have been rendered impossible in the coming term too. Labor aren’t going to run against their own record. They’re not promising to fix their own NACC, or to trash their own safeguard mechanism, useless though it is. They’re not uncapping the international student numbers that they promised to cap, or bringing forward the public school spending they promised to deliver by 2034. Albanese is not suddenly going to deliver the gambling advertising regulation or environmental protections that he personally just killed. Unless he is forced to.

Labor have spent the past three years shoring up bipartisan positions on AUKUS and defence spending, the Jobseeker rate and welfare policy, political donations reform, new fossil fuel mines, native forest logging, whistleblower laws, national security and secrecy laws, negative gearing and capital gains tax, corporate taxation, and so on and on and on. It’s all so middling, so compromised. Only a hung parliament will shift Australian politics in any significant way.

*

The short essay “On the abolition of all political parties” (1950) by philosopher Simone Weil was born of very different circumstances to ours (Europe, war, totalitarianism) and its central argument is too anarchic for broad application, but her analysis of political parties will be eternally relevant.

“A political party is an organisation designed to exert collective pressure upon the minds of all its individual members”, she wrote, and “the first objective and also the ultimate goal of any political party is its own growth”. She also wrote that political parties are “machines for generating collective passions” – sadly irrelevant in Australia’s case! – but otherwise her descriptions are all too apt. Our Labor and Liberal parties exist only to (re)gain and manage power. Lacking strong and distinctive beliefs of their own, they do this mainly at the behest of the most powerful voices: big business, big media, and to a lesser extent organised labour. The beliefs of their individual MPs and members are irrelevant in the face of the collective pressure imposed by the party leadership. Sure, the system’s stable, but our democracy’s in a sad state when its main players brook no debate or alternative views on issues such as climate change, housing inequality, education funding, foreign relations or support for genocide, let alone the other issues mentioned above. Weil’s “inner freedom”, the combination of integrity, faith and autonomy that are essential to each person’s humanity, has no place in duopoly politics; an MP’s true freedom only exists the moment they leave the party.

Weil believed that it was impossible to intervene effectively in political affairs “without joining a party and playing the game”, and this has been largely true in Australia too. But rather than get behind her proposal of abolishing all political parties, I’d suggest that community independents are an alternative solution to the same essential problem. In fact as Grant Wyeth points out in this recent essay, the emergence of community independents as a discrete political force is something of an Australian innovation (and not the first of our democratic contributions globally). Wyeth also makes the point that the rise of these loosely aligned independents is “a pro-system movement, rather than an anti-system one”. The nature of the movement is essentially conservative, and based on incremental change – dedicated to “doing the legwork to build and consolidate itself within existing structures, not seeking to tear them down”.

The affiliation of community independents through the Voices movement (and Community Independents Project) gives them structural support without compromising the individuality of each candidate. This allows the distribution of resources and the sharing of research and ideas without the yoke of party loyalty. There are no penalties to these candidates for voicing personal opinions or voting in the interests of their electorate (for example when that contradicts the official position of a major party).

Each Voices-affiliated candidate represents a community-based organisation, with its own fund-raising system (often supported by Climate 200) and organisational structure. The candidate reports to no-one above – it’s a bottom-up arrangement. To their constituency, the promise is clear: this candidate has emerged from the community, with community support, who consults with and represents this community. This compares to a major party candidate who’s often parachuted in, selected via complex factional deals, representing their party over all else and willing to suppress any and all personal opinions for that party. Independents are an expression of the (liberal) faith that individuals are entitled to a political voice, and can be trusted as representatives; more than this, each independent elected is a sign from voters that a competent regular local is more likely to represent them than would a major party. If there’s anything radical about such a view, it’s a radically cheerful, egalitarian optimism.

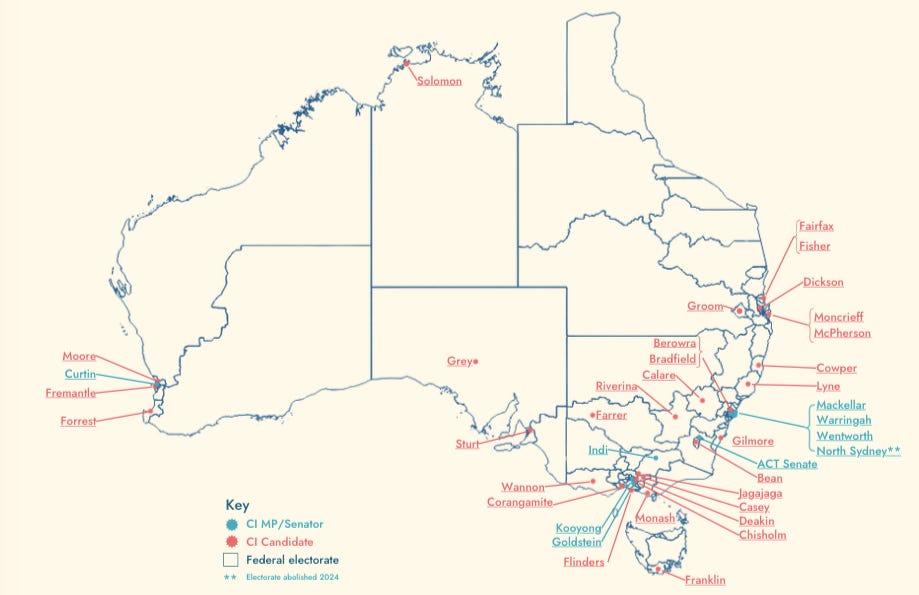

In the 2022 election, eight such community independents (aka the “teals”) were elected into the lower house, and they were mainly of a particular type: upper middle class white women representing relatively wealthy electorates won from Liberals. This time, there are 38 official “Community Independent” candidates running, and they’re fighting not just to retain these seats but also to win lower socioeconomic and regional seats from Labor and the Nationals.

The community independents have the potential to disrupt Australian politics for good, which explains the slightly manic attempts to smear them by News Corp and Coalition sources in particular. The remarkable thing so far is how flat these efforts have fallen. Nothing has stuck, no scandals have been uncovered, and none of the independent politicians have been intimidated into silence. The legitimacy of independent MPs, and their right to contribute, remains entirely unassailed. In parliament, they worked together when necessary, spoke out when appropriate, mounted campaigns representing their particular constituencies, and each maintained their independence. In short, they’re what you’d hope for in an MP.

Major-party representatives often try to make the case that you need big parties to handle complex legislation and the huge workloads of modern government, but the more realistic observer would note that big parties are much more likely to produce seat-warmers who just do what they’re told, while the offices of independents are the hardest-working in the business, and also the most likely to collaborate on improving legislation.

The most consequential issue for the voter, the duopoly insists, is that an independent candidate’s influence is limited to one parliamentary seat, so your vote is wasted on them – your MP will always be sitting at the kids’ table instead of in the cabinet or caucus. Perhaps there was some truth to that when there were only a handful of indie MPs. However should they collectively gain enough seats to force minority government, with or without minor parties and other independents (Bob Katter etc), this remaining argument against electing independents collapses.

Albanese and Dutton are still peddling the ridiculous line that they won’t do deals to get into government. Of course they will: each would negotiate away their right hand for the nation’s leadership. Bob Brown recently wrote an excellent primer for crossbenchers entering into a minority government, and he advised they seek a formal power-sharing arrangement in advance, possibly with cabinet representation. This would guarantee budget supply and confidence. However he proposed a caveat: that crossbenchers should be able to move no-confidence motions themselves if the government engages in malfeasance or criminal conduct. He believes policy goals should be included in a formal power-sharing arrangement (as happened in the Gillard government’s deal with the independents), and also that “the teals would be in a much stronger position if they were to caucus and collectively negotiate rather than be picked off one by one in an auction of parochial advantage”. Otherwise they will become mere vassals.

It’s too early to make detailed predictions about the coming election, other than to say that if he needs to, Albanese is much more likely to negotiate with the community independents than the Greens, whom he hates. (Perhaps he’ll need both, but I doubt it.) The entire community independents movement will be put to its first major test in such a negotiation. As Brown says, “The cross bench will leave millions of voters disillusioned if it does not negotiate a brace of breakthrough national policies such as making housing affordable, ensuring real climate action and ending native forest logging.” This will be the moment when all the optimistic promises of the maturing movement strike political realities. No pressure.

There are many positives, and a few serious naivetes, about the community independents but I don't think you could actually create and run a government (prime minister, other ministers, etc.) in a Westminster style system without the intermediary structural scaffolding of parties. But that doesn't for a moment mean you need a duopoly and majority governments. The ACT did quite well with a shared Labor/Greens government (and things are going a bit backwards since Labor no longer NEEDS to play cooperatively), the Gillard government did quite nicely with agreements with the Greens and independents, and many European countries do just fine with multiple smaller parties (which might be the optimal scale) forming changing alliances and coalitions.

Hi Nick, I'm a first time reader, and thanks for writing a great article.

On Bob Brown's article, you appear to read this differently to me. I took Brown's proposed strategy to be a direct alternative to Andrew Wilkie's "no deals" strategy. If so, that means that the crossbench has at least these two options available to it, and the Greens will take one strategy and the community independents will take the other.

Brown's strategy is of course predicated on a party that expressly gives confidence to the ALP and no confidence to the LNP. And it requires a formal coalition to be formed to govern, which can increase involvement in governing from the crossbench at the cost of some political freedom.

Wilkie's strategy is to vote on everything on its merits. This keeps the crossbench outside of the government, but keeps them entirely free to accept or refuse policy compromises on their communities' behalf.

Both these strategies appear to have their pros and cons, so I don't think one is inherently better than the other. And of course, depending on the results, the major parties might be able to choose who they work with in minority, or one or the other party might be forced to work with both.

Hopefully, in the future the crossbench might get even larger, and then perhaps more forms of cooperative governance might be enabled. A super optimistic view would be a multi-partisan government of the most honest and collaborative MPs available. Maybe something like that could be the best of both worlds, who knows?